“The exchanges that are produced between images and images, sounds and sounds, Images and sounds, give the people and objects in your films their cinematographic life and, by a subtle phenomenon, unify your composition.”

— Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematograph

There are very few people on camera in Still/here, yet, as the opening monologue tells us, through each brick they laid and each breath they took, they are still here. Christopher Harris apparently was heavily influenced by Bresson in his usage of sound and the way he creates almost two levels of experiencing the film is something that will stick with me for a long time. It isn’t so much usage of sound to support the Image but rather a way of creating a contrast. In this way, the film early on provides a framework through which to view it, but it never overexplains itself. Rather this framework enhances the freedom the director can take.

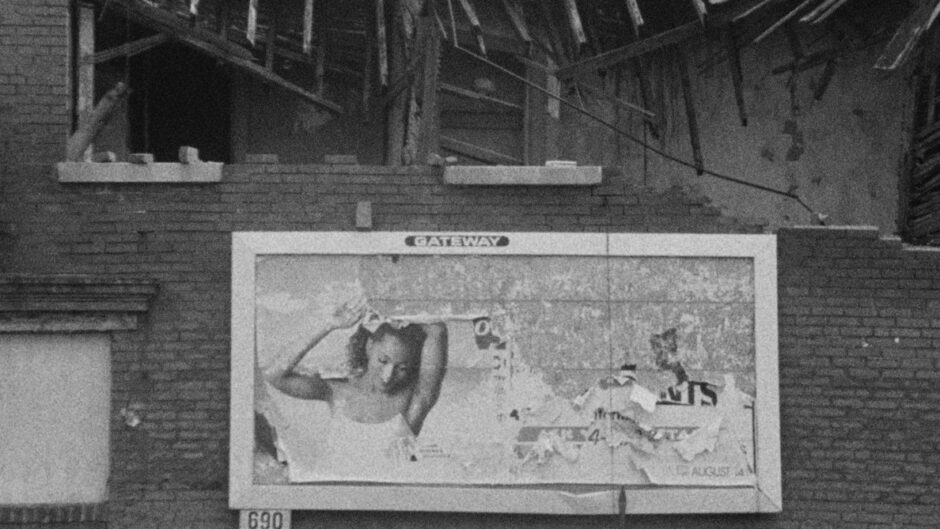

A quote at the beginning of the film, taken from an interview with Photographer Roy DeCarava, emphasizes the contribution of each singular worker towards the buildings and roads we see every day. It also primes us to view the destruction of the city as a destruction of the people and how, since the buildings are left to deteriorate, the workers are abandoned as well. And there are a lot of ruins in the film. Most of the one-hour runtime is filled with broken houses, streets, walls and constructions, all withered down by time and the people in need.

I guess this destruction is in a sense the logical outcome of a capitalist society and I agree with Harris that, in the end, this is what the people wanted. Through the politics chosen and the decisions made, they inevitably caused the city to look the way we see it now. The sadness he creates through the contrast of sound and image while showing us no traditional plot is astounding. The absence of life is highlighted in each and every second as we travel through the city of St. Louis, admiring the images of countless ruins and wondering what led to this. Like the movie’s inspiration Germany Year Zero, the city had been suffering, but unlike the famous original, the destruction has rarely been acknowledged for St. Louis.

In the Q&A, Christopher Harris explained that his goal was to exhaust the image by extending each shot far beyond the conventional point of cutting. The viewer feels that choice all the way through, as we really get to admire the imagery. This also applies in a way to the sound, in the form of an increasing prominence of what normally are considered background sounds, such as a telephone that never stops ringing; or a doorbell that is never answered. Both these things create the effect that the viewer really starts looking, contrary to other films, where scenes often are cut before one has the chance to really see the image. This becomes especially significant considering that the film captures only a snapshot of a city and its people. Both have existed before Harris shot his film and both will live on long after he finished.

I am also beyond grateful to have seen the film in the beautiful 16mm restoration. Apparently for most of its existence the film has been basically unavailable as no copies existed. Only the inclusion in recent festivals and university courses as well as then the restoration helped give the film a new life. Harris told me after the film that he considers the format to be essential to the film. He mentioned that he could never work with digital, as the finite characteristic of film was what fueled his creativity. The endless possibilities of editing digitally drove him mad, leading him to abandon it completely. This limitation forces the viewer to be there in the moment but no second more or less, just until the film runs out.

Seen at the 27th Videoex 2025, in the section “Artist Focus: Christopher Harris”

Jérôme Bewensdorff